Back in 2013, I wrote a series of 20 pieces in 20 days for MMA Fighting as the UFC turned 20. Did I have six months to write them all ahead of time? No. I literally wrote one piece per day, for 20 days straight. It was like writing a book with a 20 day deadline. Looking back on this, I must have been out of my mind. But, here they are. If you prefer to read on MMA Fighting, here is a handy link: 20 Years in 20 Days by Chuck Mindenhall

- If 20 years all at once is too much, you might enjoy this piece from my days at ESPN instead: Fifty Reasons to Love Mixed Martial arts

Jump to a year:

2013: A countdown in reverse

The improbable anniversary, moats, and the fountain of Swoosh…

The UFC’s history can be broken into four epochs that are all as different from one another as Jens Pulvers eyes: The Spectacle, The Dark Ages, The Reimagining and — finally, after many millions of dollars and blind lunatic faith — The Sport.

The earliest ideas were right in spirit but brutal in everything else. It was conjured from shrewd minds that decided to act on the eternal fight game question: What happens when a boxer fights a karate expert? What happens when a sambo player takes on a judoka. What happens when Bruce Lee crosses Dan Gable, or Mike Tyson faces Chuck Norris? Can Mortal Kombat be a thing of creative nonfiction, if done correctly?

Finally, right before things like “The Internet” began to harvest us, somebody decided to find out. Or, somebodies. It was the curious collective of Rorion Gracie, Bob Meyrowitz, producer Campbell McLaren and Art Davie who imagined the first fight game hotpot. Violence? Violence! They discussed moats and electric fences and barbed wire but settled on simple chain links in which to confine participants.

Naturally Colorado — my native state — was the first to house the UFC back in 1993. The reason being: the Centennial State had a loophole that allowed for bare-knuckle combat without all the red tape. It was the old West. Leadville still had whisky on its breath. The Manassa Mauler (Jack Dempsey) came from the mines, and Sonny Liston — who said he’d “rather be a lamppost in Denver than the mayor of Philadelphia” — cast a big shadow throughout the city. The Sabaki Challenge was an underground effort that for years prepared the Mile High City for the “Octagon,” a name chosen for its ominous ring (and its ominous associations to a 1980 Chuck Norris movie of the same name). Well before then, though, in the late 1980s-early 1990s, late-night television was littered with commercials that showed the crude, insane footage of Sabaki.

We never flinched. “Vale Tudo” felt more like an uppity red wine than anything to balk at.

The first UFC was a combat medley dreamed up in April of 1993 as most likely a one-off, something that should never have had legs to reach 1994, much less something as ridiculous as a 20-year mark. It was a spectacle, ran courageously as a spectacle, in which flirtations of death were the entire romance. It was 10 notches to the extreme of the grim trade of boxing — two men enter, and one man leaves. (This, of course, was always a baloney. The game was never without a referee, even in the gruesome beginning. Always three men left).

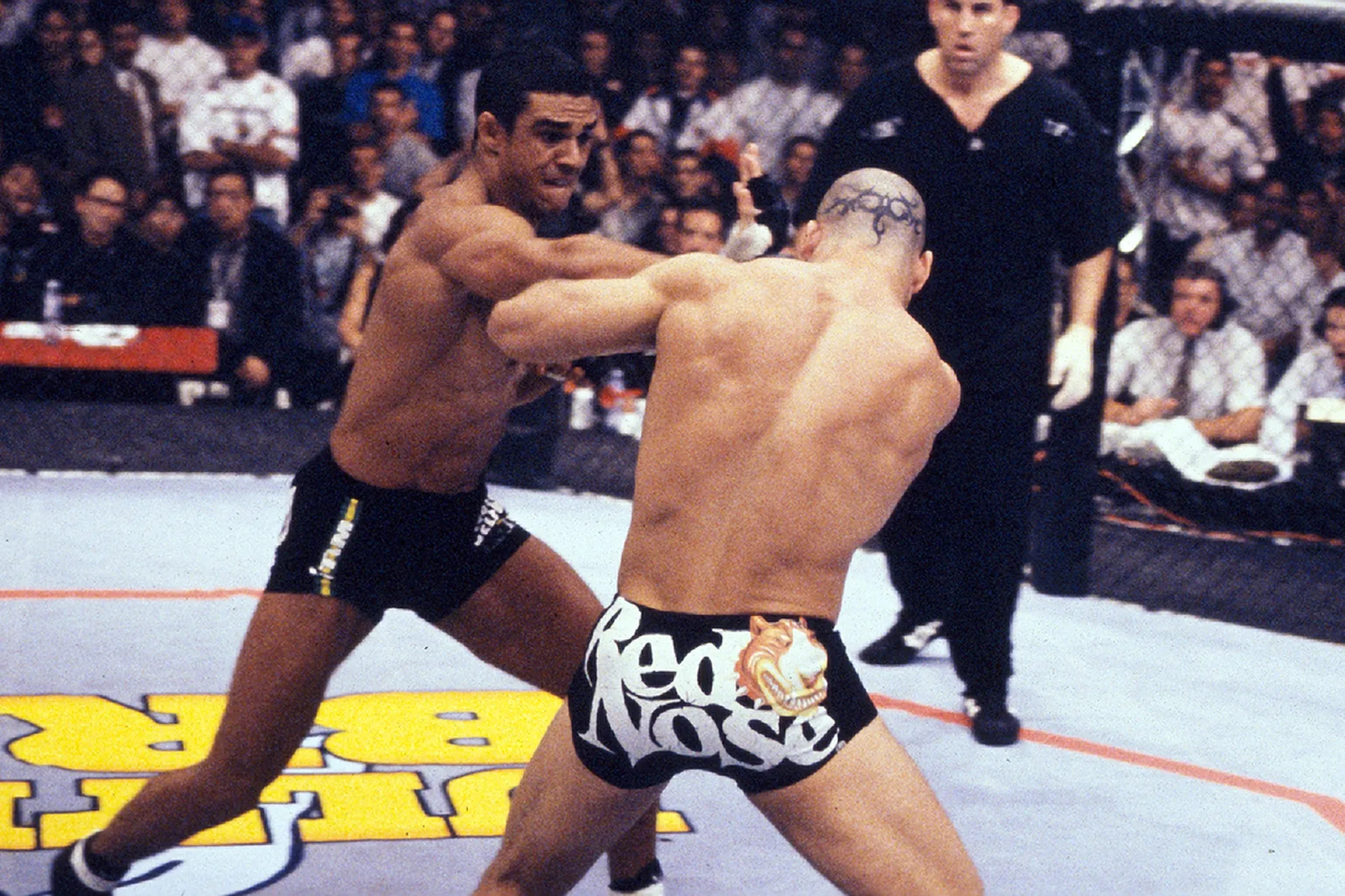

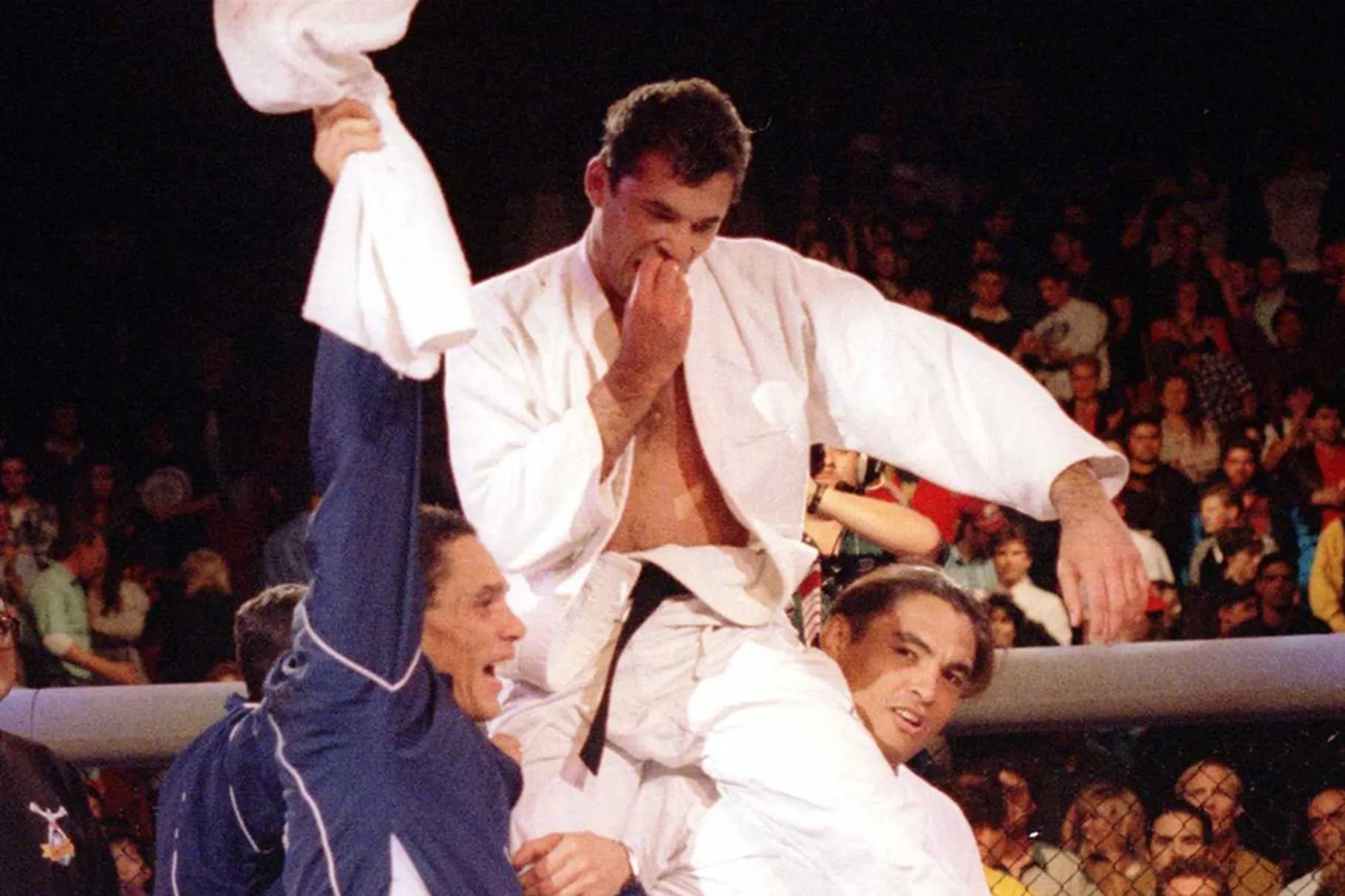

But it went on and it went on. The skinny Royce Gracie emerged as a soothing presence in the land of mustached beef and muscle. Through its crudest smoke Gracie’s poise and refinement rearranged our perception of what works in fighting. Already, perceptions were being changed.

Yet right before the turn of the century, the UFC was literally being tamped out into extinction. The old promos that proudly got behind its bloodsport were now only appealing to a basement niche with single naked light bulbs. Politicians, led by senator John McCain, were scrubbing it with sanitizer. Cable providers, which houses the pay-per-views, shut the UFC out. New York, which is liberal in everything other than hybrid fighting (liberal even in piecemeal fighting), all but booted the UFC from Niagara Falls (and from everywhere) back in 1997.

That was a bad moment. Not only did it send the UFC off to backwater Alabama on the last fight out, but other states, cities, vocal leaders and herded cattle followed suit in blacklisting the UFC. The vogue at the turn of the century was to pinch your nose at “human cockfighting.”

That’s why, in the year 2000, the UFC was more synonymous with the courtroom than it was the Octagon. Meyrowitz was tied to a dying animal. The spectacle was in its Dark Ages, and should have petered out. It was like MMA’s e era of Prohibition, only it happened just a dozen freaking years ago when Technicolor TV was already a thing and Destiny’s Child was cranking out hits.

Then…well, then you know the rest. Things turned around. It’s like a momentous blur.

It was the Fertittas and Dana White, the Italian name Zuffa chosen at random, a fed-up Meyrowitz selling the dying franchise for a song (two million bucks)…Atlantic City, Donald Trump with his olive branch, Las Vegas, the construction of the unified rules, the thud of UFC 33…Bruce Buffer, Joe Rogan, indoor pyrotechnics, baby steps to sanctioning, Chuck Liddell and his Matrix tattoo down the side of his Hun-like head…Randy Couture, B.J. Penn, Pulver, The Best Damn Sports Show, Ken Shamrock getting busted up by Tito Ortiz once, twice, thrice…Big John, TUF staked on $10 million of the UFC’s own bleeding bank, and that crazy cast of spritzing wallbangers…Koscheck, Leben, the cult of Jason Thacker, the “do you want to be a f—ing fighter” speech, into Forrest-Bonnar and a fight on free TV, the ridiculous roulette and a million new eyes…further TUFs, Georges St-Pierre, Matt Hughes, Matt Serra, Anderson Silva, the purchase of Pride, the purchase of the WEC and IFL and all fight game acronyms…Marc Ratner breaking into new frontiers, UFC 100, Dana White threatening to jump off the roof of Mandalay Bay with record buy rates…the “don’t leave it in the hands of the judges” maxim…Canada, Toronto, 55,000 people in Maple Leaf blue hues…Australia, sheiks in Abu Dhabi, England, Ireland…fight night media scrums, Lorenzo Fertitta like a silver sphinx and Dana more and more audacious, Brazil, Versus…then FOX, mainstream press, the shrinking of Kenny Florian through the weight classes, followed by the rise of Kenny Florian[‘s hair] as a broadcaster…Cain Velasquez, the lighter weight classes, Edgar, Aldo, Cruz, Barao, flyweights, then the women, Rousey, Tate…Chael Sonnen out of left freaking field, Buffer on magazine covers like James Bond, Jon Jones and Nike and Gatorade and world tours and the brightest spotlights.

It doesn’t make complete sense, the UFC’s trajectory. The thing was built-up, torn down, rebuilt, recast and legitimized, and now it’s casually in the net worth ballpark of “two billion dollars,” according to the reticent Lorenzo Fertitta. Given that it was created and bottled to be a civilization-decaying spectacle, it’s crazy to even write this: In 2013, the UFC is on broadcast television. It is the flagship of FOX Sports 1. We are seeing promos for TUF during the World Series. Jon Jones is wearing the Nike Swoosh.

Jon Jones has his own shoe in a sport that goes barefoot.

If there’s been one constant for the last 20 years, it has been hyperbole. Each fight card is a clean slate of enthusiasm. Illusion has stayed in business as long as regrets. But it’s not illusion nor hyperbole to use Dana White’s running mantra for the last decade: MMA is the fastest growing sport in the world. Given the ashes it rose from, this is a fact.

So, to commemorate 20 years of UFC, this is a countdown to 1993. I’ll work backwards beginning with this long-winded introduction in our present year of 2013. Better to start with these lush times, and head backwards into the wilderness of Rome.

These 20 entries, spread over 20 days leading up to UFC 167 on Nov. 16, will not be comprehensive, as I’m more of a quirkist than a biographer. But I’ll try to hit on key points, of which there are so many to choose from.

2012: FOX, docs and two cards in peril

In 2012, the UFC’s year of mainstream infiltration and global takeover was hindered by injuries, bad math and a card that vanished right before our eyes.

It was almost as if the UFC existed just to arrive at 2012, where it could showcase itself through a national broadcast partner and laugh at two decades worth of naysayers. And there was something legitimately poetic (not to mention fitting) about seeing Cleatus, the broad-shouldered FOX robot, alternating airtime with Nate Diaz and his dual-action middle fingers.

By 2012, the UFC had arrived. But not without a triage unit.

For all the bells and whistles and spray paint to cover the preliminary blood spill before each telecast, there was usually a trail of wounded that disfigured whatever it was that was first intended. Poor Joe Silva was afraid to check his voicemail in 2012, because it was usually a moaning voice at the other end, telling him that the show would just have to go on without him. Behind the scenes, Silva went from matchmaker to makeshift card cobbler on a running loop. Just look at this litany of horror.

Pay-per-views in 2012 became heavily edited fourth and fifth drafts that bumped people like Rich Franklin into starring roles against Wanderlei Silva at UFC 147, in rematches that never occurred to us. UFC 149 in Calgary? It might have been better to just use the spray paint on the camera lens and pretend it never happened. Shawn Jordan and Cheick Kongo essentially engaged in battle at the line of scrimmage for three rounds, which felt like watching a pickpocket toiling to steal our disposable income for 15 minutes. That was, mercifully, the worst of the PPVs that happened.

And that was still one better than UFC 151, which actually didn’t happen.

UFC 151 was the nadir in the year of broadcast television, Murphy’s Law and ultimate suffering. Sokoudjou, a Cameroonian fighter who was always a mysterious figure of unknown potential after knocking out Lil Nog in Pride, injured Dan Henderson’s knee in training. Henderson, who was getting his title shot against Jon Jones and didn’t want to squander the chance, wasn’t exactly forthcoming with this information to Joe Silva. At least not immediately. By the time he fessed up just eight days before his fight, the UFC was left scrambling for a replacement. That’s when Chael Sonnen raised a stoical hand to volunteer, and became the unlikely hero of a card he had nothing to do with.

And that’s when Jon Jones, who turned the fight down, became something other than a 24-year old phenom, and Greg Jackson became a “sport killer,” and Dan Henderson disappeared from contention, essentially, forever. UFC 151 disappeared along with him. And now there’s a hole in the PPV lineage with origins back to Sokoudjou, who was just trying to present himself as a reasonable simulacrum of Jon Jones in an afternoon roll. The fight game, it can be said, is all about fate.

Of course, that all went down in late August. In April 2013, we were still dealing in the Sonnen/Jones saga, after they coached opposite each other on TUF, all because Sonnen had — in a moment of crisis — been so good as to volunteer his services.

The end result was a mini-revival of the Dark Ages (which we’ll get into next week in between the years 1998-2001).

Yet, while all these things were playing out, the flyweights entered the marketplace. To introduce the weight class, the UFC hosted a four-man tournament that began in Australia to crown its first ever 125-pound champion. The entrants were the maestro Ian McCall, the veteran Yasuhiro Urushitani, and two names who’d been masquerading as bantamweights — Demetrious Johnson and Joseph Benavidez. The flyweights were like electrons…no, they were motorcycles swirling around each other in the sphere of death, just a bunch of frenetic energy that strained the naked eye to comprehend what it was seeing. The flies sent play-by-play men into paroxysms, and stoned dudes into fits of giggles.

But as they fought, people began to wonder: Do I like this? Some people didn’t. At least not at first. The idea of a 5-foot-nothing homunculi trading punches wasn’t the swooping allure of big-bodied headhunters. From the privacy of the couch, these guys, for all their technique, looked like flickable paper footballs. But from the first bouts in Sydney, the flyweights went about making us into small-fry aficionados.

“At that time, when the UFC was thinking about the flyweight division, I just came off a loss to Dominick Cruz and it was only a rumor,” says Demetrious Johnson. “I was getting ready to fight Eddie Wineland at 135 pounds, so at that point my mind wasn’t even focused on 125. But then eventually they pulled me out of that fight, and said we’re actually going to do the flyweight division, and you’re headed to Australia.

“I said, Oh, sweet, I’ll be fighting guys who are like 5’3″ and 5’2″, instead of guys who are 5’11″ or 5’9″.”

Of course, Dominick Cruz invented the flyweight division. He’d already set back Johnson, and he’d beaten Benavidez twice, leaving him nowhere to go. And for all the knocks on flyweight power, Benavidez was hell-bent on changing those notions with a second-round knockout of Urushitani.

“Mighty Mouse” and McCall fought at a blistering pace for three rounds. The fight, par for 2012, ended in controversy. Because it was a four-man tournament, the UFC had made a provision to allow for a “sudden victory” round in the event of a draw. Johnson was declared the majority decision winner but, when it was revealed that one of the judges made an error in calculating his scorecard and the fight was actually a draw, the decision was converted into a no contest.

“To get the win, and then go into the back and hear Dana White say, ‘it was a draw,’ man, it sucked,” says Johnson. “But at the same time Dana gave me my show and win money, and we both got fight of the night, so that was great. I was a little frustrated just because I wanted to go on and fight Joseph [Benavidez], but Matt Hume my coach, said, ‘it’s okay, you’ll get to fight Ian McCall again, you get to go to 125 again, and you can do your diet right.’”

They did fight again in June, and Johnson won the decision. He went on to defeat Benavidez at UFC 152 in Toronto to become the first ever flyweight champion, and he’s beaten everybody he’s faced since then.

The rise of the flyweights, and particularly Johnson, was one of the silver linings in a year that was filled with ups and downs (with far more downs than ups).

2011: Business as usual (even as Strikefarce restores itself as Strikeforce)

Here is 2011, in which Zuffa purchases Strikeforce and Clay Guida is relegated to Facebook. vanished right before our eyes.

On a single night in 2011, the best fights of the year took place. Dan Henderson and Mauricio Rua nearly killed each other for five rounds at UFC 139 in San Jose. That fight was a tale of halves — Hendo early, Shogun late.

Happening on the other coast, Michael Chandler and Eddie Alvarez struck a match to the barn using skill, guts and — in a strict manner of speaking — idiocy. No two men with any sense of preservation can be expected to fight the way they did in Hollywood, Florida. No sane men with careers still to go.

Defiantly, though, they did.

The moon wasn’t full that night. It was a standard waning crescent. But somehow the Fight Gods were in an uproar. Even fight game atheists found themselves overwhelmed by the products of Nov. 19, even if it was more chaotic coincidence than anything celestial.

Yet, both those monuments of 2011 came in under the radar because everyone was still sweeping up the confetti from the week prior.

On Nov. 12, the UFC and FOX put on its first broadcast show framed around a single fight, Cain Velasquez versus Junior dos Santos, not out of contractual obligation (that didn’t kick in until 2012), but out of the something like the goodness of giving. Historically, this was the first ever fight night bonus awarded to fans. Dana White and FOX president Eric Shanks were like kids who couldn’t wait until Christmas morning for us to open their gift. This undertaking was so crazy that Clay Guida (at the time unhindered by strategy) and Benson Henderson (pre-Toothpickgate) battled on Facebook, and this didn’t feel entirely like buzzkill.

You might remember the set up. Velasquez had played matador against Brock Lesnar a year earlier at he very same venue in Anaheim, and dos Santos had just smoked Shane Carwin at UFC 131 in Vancouver. It was two bounding momentums colliding on free TV. (Did they mention it was free? This is a gift you ingrates! Gratis!). And what a broadening it was with so much going on. Protective diehard fans were getting territorial by the forced sharing of their sacred product with something as amorphous as “mainstream” and “casual” people (both synonyms for “despicables”). These feelings were roiling underneath all the hoopla whether anyone was admitting it or not.

The fight itself lasted a very ho-hum 64 seconds. Dos Santos hit Velasquez with an end-game right and flew off to Brazil with the belt. It played out as something less than the CliffNotes to the vast and varied sport of mixed martial arts for those getting their introductions. It was more like a pull quote from War and Peace.

And still, none of these were the actual story of 2011.

The real story was Zuffa’s purchase of Strikeforce back in early spring. Strikeforce had burst the seams of its regional presence in San Jose, and was now a clear second to the UFC. When Strikeforce, with all its intriguing parts — Nick Diaz, Dan Henderson, Gilbert Melendez, Luke Rockhold, Ronaldo Souza, Gegard Mousasi, the great Fedor, et al — began shopping itself, Zuffa did what it does at the end of the day and when it is what it is.

It purchased the competition. The partition was about to come down to create a million new previously only dreamed of fights. Was Gilbert Melendez really a top two or three (or one) lightweight? Heaven forefend, we’d be finding out.

Only, you know, we didn’t. Not right away. Showtime was still the hub of Strikeforce, and Dana White and Showtime officials have never been what you might consider BFF. It was a relationship that from the beginning was frigid, before it thawed, before it became glacial.

“At the time [Zuffa purchased Strikeforce], it was exciting,” says Strikeforce’s middleweight champion Luke Rockhold. “You thought about the crossover fights, and you thought about all the possibilities. It was really interesting at first.”

And then it became something else. It became uncertainty. The partition stayed up. Strikeforce was Zuffa’s property, but Dana White was flinging around this cryptic double-speak that sounded something like “business as usual.” Scott Coker, who was the soft-spoken ringleader of Strikeforce, kept saying that they’d have more details in a couple of weeks. The fights went on stoically, but the “it’s a matter of time” mantra caught fire. Strikeforce with no independent future hobbled along for another 18 months, while certain pieces began migrating to the UFC, and others found themselves on the dreaded “black list.” The “black list” was created to protect Showtime/Strikeforce fauna from poaching, which felt like imprisonment to the lingering stars who were forced to ride out the duration.

“Once it started settling in, that some people were stuck and there was no crossing over and none of that was going on, it was kind of disappointing,” Rockhold says. “I felt kind of trapped for a while, so it was a lot of mixed emotions.

“It was sad, too, because we had the PPV opportunity and a lot of things going for Strikeforce. I wanted to see Strikeforce survive and live on. I immediately thought it was going to die. But as a fighter, you always kind of wanted to be in the UFC. That’s my mentality — just being able to prove yourself against the best in the world, and fight those best guys. That was an exciting factor and it definitely played in. I think there were more positives than negatives coming out of it.”

Rockhold won the Strikeforce belt in 2011 in a crazy fight with Ronaldo Souza (who hasn’t lost since). The rematch became the elephant in the room in a division that just didn’t have much depth otherwise.

“That was a tough time,” he says. “You’re waiting around. I had to fight Keith Jardine in my first title defense, and I was pretty upset about that. He’d never fought at 185 and was coming off a draw at 205.

“It was just a matter of when it’s going to happen. You hear all these guys like Daniel Cormier getting merged in and getting the opportunity to make the bonuses and all the little things that come with the UFC. Those guys were rubbing it in with me. The sponsors, and everything was better at the time in the UFC. It was really hard to get sponsors in Strikeforce because everyone knew it was going to die and they didn’t want to break into Strikeforce and pay the tuition and all that when there’s no security in their money.”

Rockhold would end up defending his title twice in 2012, against Jardine and then against Tim Kennedy. Mercifully, at the end of 2012, the partition really did come down. Most Strikeforce fighters were fully integrated into the UFC roster. It was a matchmaker’s paradise. The most notable who didn’t crossover was Fedor Emelianenko, whom Dana White and Lorenzo Fertitta have a story about from the time they journeyed to faroff Russia in hopes of coaxing his cathedral calm into the Octagon.

What happened on that fabled visit to Stary Oskol remains a fight game mystery, one that will surely reveal itself, in pieces, throughout future scrums.

2010: ‘Ferrari World,’ Sheikhs and the WEC comes calling

A look back at 2010 — when the WEC was being merged with the UFC, and Anderson Silva was going berserk in Abu Dhabi.

Since the advent of mustached strongmen, the circus has traveled around on the rails and pitched multicolored tents. Part of the attraction was that the attraction came to you. And part of the UFC’s model is similar — the idea is to travel around to whatever sector of the globe is ready to embrace it. Instead of a tent, they pitch an Octagon. And unless you live in the Falklands or in upstate New York, chances are the UFC will end up in your general area sooner or later.

When the UFC decided to go to Yas Marina in Abu Dhabi in April of 2010, this felt by far like the craziest thing the promotion had attempted. It wasn’t that they sold off a minority portion of the company to Sheikh Tahnoon, or that it was headed to the Middle East, or that the event would be held alfresco under the wheeling constellations just like Tunney-Dempsey back in 1927 at Soldier Field…it was that there wasn’t a freaking venue in place.

It was that they were going to build a temporary arena to house UFC 112, and then tear it down a week later.

Therefore, “Concert Arena” was erected as nothing more than ephemera, just a glamorized squat house for the UFC’s visit. If that weren’t enough, it was built within something called “Ferrari World.” You could practically see the Sheikh using $100 bills as kindling for his fireplace while swirling a glass of Henry IV cognac. Laughing. Laughing. (With the flames dancing in his eyes.)

The event in Abu Dhabi was a catalyst for a lot of things. It told everyone that the UFC meant business in taking the Octagon all over the world, not just ports in Europe and Canada. That night on April 10, 2010, the UFC rolled out two title fights like a lush red carpet, and yet neither of them came off even remotely close to what might be considered “reasonable expectation.”

Frankie Edgar fought B.J. Penn in the co-main event, and Anderson Silva — who was originally supposed to fight Vitor Belfort — took on Demian Maia for the middleweight crown. Maia and Edgar were of course the sacrifices. I remember beforehand a very well known MMA journalist telling me, while emboldened by his Guinness, “Edgar might be the first fatality in the cage.” He was of course exaggerating, but the sentiment was there; Edgar didn’t stand a chance.

Turns out Edgar did stand a chance, and in fact fairly dominated the scorecards en-route to taking Penn’s belt. That was the first “say what?” moment in a night full of eye rubbing. The Silva-Maia nightcap was one of the most bizarre main events to ever have pay-per-view customers screaming for rebates. In it Anderson Silva sort of flew off the handle. He mocked and preened and went into theatrics for much of the five rounds he wasn’t even supposed to need in putting Maia away. The performance was so remarkable for all the wrong reasons that Dana White put out a piece of caution on the Jim Rome Show afterwards that said this: He’d cut Anderson Silva if it happened again. Even the greatest living mixed martial artist in the world wouldn’t be suffered such shenanigans.

(This was the context for Silva and his rivalry with Chael Sonnen, who came along at just the right moment right after. Sonnen breathed life back into Silva, just like Silva became a sort of world stage for Sonnen to reinvent himself).

A month earlier, at WEC 47, on March 6 in Columbus, Dominick Cruz defeated Brian Bowles to become the promotion’s bantamweight champion. That night was brimming with the talent of today. Look at the names that appeared on this card before Cruz — Joseph Benavidez, who fought Miguel Torres; Danny Castillo and Anthony Pettis; Scott Jorgensen, who fought Chad George; Chad Mendes and Erik Koch. The card was so stacked that Ricardo Lamas, who fights for the UFC featherweight crown against Jose Aldo at UFC 169, was the first fight on the prelims.

It was just another WEC card.

Zuffa owned the WEC, but at this point had kept the two organizations separate. The WEC had the smaller weight classes. The UFC had everything else. By October of 2010, with the UFC growing and holding more events and needing more star power to carry them, Dana White announced that the promotions would be merging. This was significant for two reasons. One, it meant existing undersized UFC lightweights could fight at 145 pounds without leaving the UFC. And two, it meant people like Cruz, Pettis, Demetrious Johnson, Benson Henderson, Benavidez, Mendes, Lamas and poster boy Urijah Faber would finally showcase their wares for those who avoided eye contact with the WEC’s blue cage.

The WEC would bring over a world of talent to the UFC.

“That was the goal — it was always to find the best fighters,” says Reed Harris, who was the general manager and face of the WEC. “We worked very hard at that. When I came into the office, I never would hear people say, ‘hey the lighting on that show was fantastic.’ Inherently I knew it was all about the fights, and that it’s all about the fighters. So we spent a lot of time looking at them, and went down to Brazil to find Jose Aldo. We did a lot of things that a lot of people didn’t do in trying to find the best people.”

Jose Aldo. The man who made Americans figure out the correct order of the vowels in Nova Uniao.

“The first time I saw Jose, he jumped out of the cage, and I took him in back with his manager Andre Pederneiras — and I’m a guy who rarely raises his voice, because that’s just not who I am — but I was yelling at him,” Harris says. “I read him the Riot Act. Little did I know he didn’t have any idea what I was saying, but he knew I was mad.

“The next show, I was in the cage after he won, and he looked at me, ran towards the door, stopped and then sat down,” Harris says. “He looked up at me and smiled, kind of like a f— you, and ever since then I’ve liked him. Now we’re very close. We spent a lot of time together.”

Harris is now the Vice President of Community Relations with the UFC. Aldo is the long-tenured featherweight champion who is hovering the top three space of most pound-for-pound lists. At UFC 142, after Aldo knocked out Chad Mendes, Aldo disappeared into a sea of his countrymen once again. And once again, Harris was right there tapping his foot with his arms crossed.

“I yelled at him to get back in the cage,” he says. “That’s his place, right? I wasn’t mad at him for doing it. It was crazy. I actually got punched in the crowd. Not on purpose. The guy who punched me looked at me like he was in shock because he was trying to grab Jose. It was just very chaotic, and I yelled at him to get back in for safety reasons.”

That Harris is now scolding Aldo outside of the UFC Octagon instead of outside the WEC blue cage marks the evolution of the times. At some point along the way, Harris knew that the bantamweights and featherweights he’d helped along, not to mention his crop of high-powered lightweights, would all be migrating to the UFC. The thing was inevitable.

“I think at some point it was just decided, look, the UFC is going to be the dominant brand in this sport forever,” he says. “Especially when all of us were watching these lighter-weight fights including Dana and Lorenzo and Frank [Fertitta], and they were seeing that they were entertaining and that people were interested. So why not add to the brand? Why not make the brand even stronger?”

On Feb. 1, 2014, at UFC 169 in Newark during Super Bowl weekend, the WEC’s elite will be on display. Renan Barao and Dominick Cruz will unify the bantamweight belts, and Aldo will defend his title against Ricardo Lamas.

2009: The UFC comes full circle, thanks to one daring adventurer

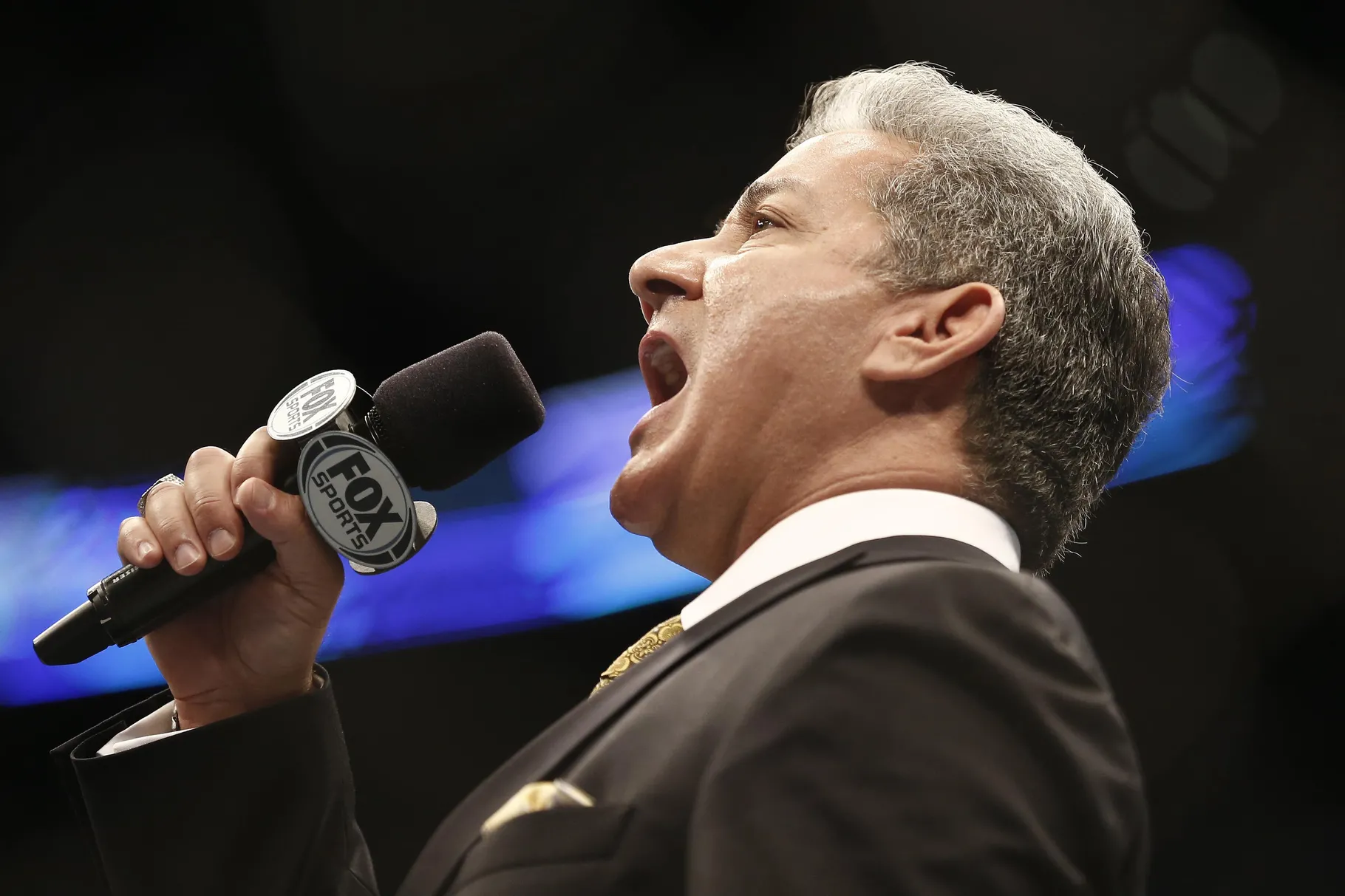

UFC 100 was monumental for a lot of reasons. But the work of Bruce Buffer that night, who unveiled the single greatest stunt on the single biggest stage, was particularly exquisite.

Maybe it wasn’t actually the case, but at UFC 100, Frank Mir looked about as happy to hear the referee say “alright, now bring it on” as a clay pigeon might upon hearing the word “pull.” It was Brock Lesnar at the other end, after all, restrained for one long last second before the shackles would come off and the rivening could commence. The only thing we required as spectators was Mir’s courage in the ordeal

And that was how we celebrated 100 events in the UFC. By feeding Frank Mir, who’d defeated Lesnar famously a year and a half prior in Lesnar’s ballyhooed debut at UFC 81, to His Sworded Thorax. A record-breaking number of households paid for the courtesy. Mir hung around until the second round, but he wore the macabre scene on his face by fight’s end.

Lesnar, ever eloquent in such matters, described it as extracting the horseshoe that had been lodged in Mir’s hind region. That was right after he began somewhat rabidly frothing about the mouth, and just before he said he was going to drink himself some Coors Light (while standing on the Bud Light emblem) and, heck, if we’re keeping it real, maybe even “get on top” of his wife later that night.

It was a lot to digest.

And that piece of theater was the crescendo moment in the UFC’s PPV numbering system, which is now careening off towards UFC 1000 and beyond. Georges St-Pierre had dominated Thiago Alves in the co-main event even with a torn groin muscle for half the bout. And Dan Henderson, to the gratitude of patriots from the Puget Sound to the Everglades and on up through the Adirondacks, knocked Michael Bisping out with a ridiculous right hand. “To this day people thank me for it,” Henderson says.

(Note: Why Bisping was circling into that power right now becomes the problem of future generations to solve).

All of this was fine in the wholesome sense. But, at the same time, all of this paled next to the hair-raising moment just before Lesnar was loosed on Mir. That was when Bruce Buffer, the evangelist of the Octagon who whips everyone into a frenzy with his introductions, pulled off the unthinkable.

The Buffer 180º — which Buffer himself modestly called a “whip turn” before fans apothesized it — was always more than we could ask for. But Buffer chose UFC 100 to unveil the Buffer 360º, a ridiculous maneuver of lithe acrobatics and aerial illusion, and he stuck the landing while pointing his cue card right between Brock Lesnar’s blond eyebrows.

Game. Set. Match.

“You know, when you do something that’s different and out of your realm, you want to pick the right time,” Buffer says. “So with that being the case, there was no other event. It would have to be UFC 100. And I didn’t tell anybody when I was going to do it. If you watch Joe [Rogan]’s video after, he thought I wasn’t going to pull it off, but I saved it for exactly the last precise moment when I was right in front of Brock Lesnar’s face.”

Buffer goes into depth about the Buffer 360º in his captivating book, It’s Time!, but words become such paltry things next to The Thing Itself. Why? There are very few moments in the fight game where flawless execution and…what, destiny (?)…come together as if cosmically ordained.

It was Joe Rogan that began challenging Buffer to attempt the stunt to begin with, after putting out a backstage video where Buffer dreamed it into existence. Then a million fans began echoing Rogan’s need to see it. The thing caught fire as the video went viral. From there the Buffer 360º became not only a matter of when and where, but of courage and mettle.

So what did Buffer do? He embraced the biggest stage the UFC had had to that moment…and, for a few brief moments, spun in levitation like a genie materializing from a bottle. It was a thing of cocktail elegance and grace.

“I knew what I was going to do,” he says. “The thing is, I don’t rehearse. I don’t plan. I like to go out there and be organic and improvise off the energy I feel from the crowd, whether it’s 50,000 or 20,000 or 10,000 people in the audience. But that night was electric. I couldn’t have for a better script as far as a screenwriter writing a movie of how it came off…it came off perfectly in my opinion. And Joe wrote me an email after that said, ‘not only did you do it, but you did it in front of the biggest, baddest man on the planet.’”

There are obvious hazards for such undertakings. Remember, Buffer tore his meniscus while doing a “grounded 360” at UFC 129 in Toronto. He was playing injured that night with a bad ankle, and as he went into his bunny hop at the end, his knee gave out. Stoically, Buffer didn’t miss any events. How’s that? As the writer Frank Curreri once said, “if Michael Buffer is fine bottle of Bordeaux, then Bruce Buffer is a shot of Jack Daniels.” That’s how.

There will of course be other monuments. UFC 200 should take place in 2016. But don’t expect to see the Buffer 540º, or even the 360º again. That bold feat is now frozen in time forever in 2009.

“I’m not an acrobat,” Buffer says. “I don’t want to say anything, because again, if something’s going to happen believe me it’ll happen because I decided for it to happen at that exact moment. But the aerial thing, the airborne stuff, that’s over.”

Over, but not forgotten.

2008: The man who first met Mr. Jones

Between UFC 87 and UFC 88, the UFC’s light heavyweight division shifted. The Chuck Liddell era came to a close just as Jon Jones snuck onto the scene at UFC 87. The man he fought was Andre Gusmao, who to this day wonders about the buzzsaw he met…

Jon Fitch was already well on his way to becoming a verb when he fought Georges St-Pierre at UFC 87 in Minneapolis. To get “fitched” meant to spend three rounds on your back staring up at the ring lights in a state of helplessness, using peripheral vision to try and avoid incoming elbows and icepicks. He was the quintessential grinder, always gritting his teeth and snarling.

St-Pierre, though, would not get fitched, not that night nor ever. He would be the dictator of wills, and win a hard fought decision that left both men bruised and in tatters. The hype around UFC 87: Seek and Destroy not only belonged to GSP in that defense against Fitch, but also to the hometown colossus Brock Lesnar, who fought in the co-main event against Heath Herring. Lesnar brought the blitzkrieg to Herring that August night back in 2008.

It was a night of moving fortunes.

In hindsight, who’d have known at the time that A) this would be Herring’s last fight in the UFC (or anywhere) or B) that this was the high-water mark for Fitch. He would live perennially in the No. 2 space behind St-Pierre after the loss until Johny Hendricks crashed a left hand through him at UFC 141. It was a mercy measure. By batting Fitch back, Hendricks allowed UFC matchmaker Joe Silva to loosen his tie.

That same night, there was an alternate on the undercard who’d been booked only after a series of injuries to more familiar names. That was Jon Jones, a generic sounding warm body who had alliteration working for him but little else. He came in ultimately as a replacement for Tomasz Drwal to face Andre Gusmao, who was also making his promotional debut, having just knocked out Mike Ciesnolevicz in the IFL. Not too many people paid attention.

Particularly Gusmao, an unsuspecting Brazilian fighter who trained under Renzo Gracie in Manhattan. Gusmao didn’t know it then, but he was the proverbial steak being slid under the door for the 21-year old former junior college wrestling champion from Endicott, New York. He made history that night by going first on the trail of “Bones.”

“I literally knew nothing about him,” Gusmao, now 36, says today. “I just didn’t know. I was supposed to fight one guy and he got hurt, so they put in another guy, I think it was Alessio Sakara, and he got hurt. I think Jones was like the fourth option of guys down the line. They said, your guy got hurt, so we’ve got this guy, he’s a wrestler, you should fight him. I was like sure, I don’t care, I’ll fight him no problem. I literally knew nothing about him, other than he had a couple of fights.”

Jones was 6-0 at the time. He was a one-two-and-shoot fighter, just raw rudiments and length. At least, that’s what he’d shown on the local circuit. But in the UFC, he began freelancing with his striking right off the bat. There were some spinning elbows and flying knees that started trickling in as the fight progressed. Even still, it felt like Jones was leaping into the deep end of things in the fabled light heavyweight division with so few fights under his belt. The following card, UFC 88 in Atlanta, featured a bout between Chuck Liddell and Rashad Evans. Those were the great heights. That’s why Joe Rogan said on the telecast of Jones, “this is a shark tank division to jump into after only nine months in the game.”

Turns out Jones was the shark, and everyone else a school of remoras. Including poor Gusmao, who knew he was in trouble the moment he laid eyes on Jones.

“I’d never seen the guy before, so when I saw him at weigh-ins I was like, man this guy is huge,” Gusmao said. “The first time I saw him was pretty much when we faced off. I hadn’t seen him before. Didn’t know about his height or his reach, nothing. So I was like, s—, because I’m 6-foot-2 and I looked at this guy and thought, wow, this guy’s big — I’m in for a long night.”

Jones used his wrestling, and some crude ground-and-pound. He also cracked Gusmao with spinning elbows and flying knees, which sort of blossomed over the course of the three rounds into something like “we might want to keep an eye on this guy.”

“When the fight was over I was very pissed off,” Gusmao says. “This guy just kept kneeing me, gave me a hard fight. I didn’t do well. One of my cornermen said, you know, this guy’s going to be a champ. I said, no man, I just fought badly. He said, no, this guy’s going to be a champ some day. And then as time went by, and now when I look at it, I’m like Jon Jones is freaking great. Even Renzo Gracie and some of my fans, they’re like, you gave this guy the hardest fight and you didn’t even know who he was.

“At the time I was very pissed off, but these days, I’m like, okay.”

Less than a month later, on Sept. 6, Rashad Evans knocked out “The Iceman” to essentially bring to a close the Liddell era — an era that carried the UFC through the mid-aughts. In the span of four weeks, between UFC 87 and UFC 88, Jones came into existence while Liddell receded into a bygone day. The future barely made a splash, while the past sent shockwaves through the fight world.

And Gusmao? He now runs a gym in Manhattan. In the fight game as in trivia, he’ll always be the guy who found out first about Jon Jones.

2007: The long stretch of L.I.E. between hard luck and gold

2007 was when Zuffa purchased Pride FC and MMA’s first big “superfights” got real. It was also when the UFC visited Houston, where strange things happened.

Zuffa’s acquisition of Pride FC was the first big intergalactic consolidation of fight game stars. Well before we were flirting with hypothetical “superfights” in 2012, the UFC was doing something about it in the spring of 2007. All it took for those icons from Japan — forever separate and living out a beautiful cult dream under the watchful eye of the yakuza — to descend upon the UFC fighters like the Great Wave off Kanagawa was something like $70 million.

Lorenzo Fertitta said at the time, “we will be able to literally put on the fights that everyone wants to see — it will allow us to put on some of the biggest fights ever.”

At UFC 75 in London, newly crowned light heavyweight champion Quinton Jackson — a Pride veteran who’d signed with the WFA before the UFC snapped that promotion up too — welcomed reigning Pride middleweight champion Dan Henderson into the Octagon. Jackson “unified” the belts in front of five million viewers on Spike TV. These were the fights people wanted to see (especially for free, and even on tape delay).

And that fight was less memorable than Forrest Griffin’s rude treatment of Mauricio Rua at UFC 76. When Griffin sunk the rear naked choke late in the third round, he did a hot lap around the cage with his arms thrown up incredulously, as if it’d never dawned on him he could win. The wall was down. The wall was down!

Only a couple of weeks after the purchase of Pride, with all the potential elixirs still in the air, the UFC 69 went down in Houston. The main event was presented to the public as a gift horse to second chances. Matt Serra, who had won the “Comeback” season of the Ultimate Fighter, would get a crack at welterweight champion Georges St-Pierre. People were left to invent intrigue in the fight, because Serra — bless his heart — was vastly outclassed. The Long Islander was built like a hydrant, but there was simply no way. There was no way. Big dogs lift their legs to hydrants. St-Pierre was a 10-to-1 favorite.

“It’s going to sound clueshay,” Serra said in the promos leading up, “but to win that belt would be a dream come true.”

The dream came true. Serra, whom everybody thought would try and do what Matt Hughes couldn’t — that is, taking GSP down — ended up clubbing him with a right. Then hurting him with a left. Then swarming him with a barrage of muscle-intensive end shots that left St-Pierre in the reclining arms of history.

To this day, that Serra KO of GSP is not only considered the greatest upset of all time, but a cautionary tale for the ages from GSP’s perspective. It was Matt Serra who invented the puncher’s chance in MMA, which has made the betting public think twice whenever a lopsided fight gets booked. He provided an example to what’s meant in the whole “four ounce gloves” thing.

Standing in Serra’s corner that night alongside their coach/mentor Ray Longo was Pete Sell, Serra’s longtime friend who’d lost on the undercard to Thales Leites. His face was still bulging with trauma from Leites’ elbows. Yet he stood with Serra anyway, just like he had been since he was 17 years old. And in the elation of Serra’s greatest moment, Sell celebrated with him like a buddy who’d lost all his money at the blackjack table yet was at least watching his friend cash in ten tall stacks of chips.

“I was upset that I lost,” Sell says. “I think it was right before that fight that I had that Scott Smith fight, and in that fight, I won! I won the fight. Then I ran in like an idiot, and I would have hit him with a big uppercut, the first time the whole night I dropped my hands, and that’s when I got caught.”

Turns out 2007 was a year of What Could Have Been for Pete Sell. For Serra, it was the year that was, is, and always will be.

“So against Leites, it was supposed to be my turn,” Sell says. “Things didn’t go my way. I was upset. I was kind of down in the dumps after the fight. But I was in Matty’s corner, and the whole Longo Team, we just stick together.

“And my boy Matty frickin’ knocked out the impossible,” he says. “Everybody at that time had GSP on a pedestal. He was just so unstoppable. I think Matt Hughes got the armbar that time, but that was the only time he lost. After GSP knocked Hughes out a couple of times, it was this guy’s unbeatable. If you look at the beginning of Matt’s career, when he fought Shonie Carter, people were writing that off. He wasn’t that good. People were saying things like Matt Serra has no chin. People were taking a crap on the guy, so it was nice to just see him have his moment when he knocked out GSP. Because nobody in the world thought that would happen. Nobody gave the guy a shot. I was so happy for him that night, what a great feeling.”

In his post-fight interview with Joe Rogan, Serra said his win was “possibly the greatest upset in UFC history, [though] I’m not saying it.” It was. Serra would hold the belt until the rematch at UFC 83 in 2008. Sell would fight Nate Quarry in September, and once again lose a fight that he was on the brink of winning. In 2007, with all the madness going on in the UFC, Sell became the master at snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

As for Georges St-Pierre, what happened at UFC 69 in 2007 can now be packed neatly into his greatness. Nobody in the fight game treats complacency with such disdain as St-Pierre does today, and it was Serra that made him compulsive in guarding against it.

2006: Spider and Ice

In 2006, Anderson Silva was served up a plate of Chris Leben…and Chuck Liddell lived as the greatest rock star the fight game had ever known.

In retrospect, throwing Chris Leben in there against Anderson Silva wasn’t very nice. Leben was going to do what Leben does in welcoming Silva into the UFC, which was move forward throwing bombs willy-nilly with his chin flashing neon and wide open for business. He’d already proven himself to be that rare fighter; the more you hit him, the more dangerous he got. When you hit him good, I mean really good, that’s when he bounded forward on those famous toddler legs returning fire, like an indestructible mass of orange hair and nail polish returneth from the grave.

It was almost masochistic, watching him fight. It was certainly masochistic watching him fight Silva.

Silva sniped Leben from afar, from inside, from up high, from down low, from acute, right and obtuse angles, with his knees, fists, open palms and the business end of his elbows. It was fight game geometry, and the whole thing lasted an absurd 49 seconds. Joe Rogan turned up the shower pressure of accolades from the start: “This is a different kind of striker,” he said. His was “a ballet of violence.” And none of it was hyperbole.

Silva wouldn’t lose a bout until the 17th time he entered the Octagon, as a 38-year old boogeyman whose striking reach was still as long as his afternoon shadow.

And if Anderson Silva was the future in 2006, then Chuck Liddell was the glorious present. He was the reason that MMA was the new rock & roll. The robust mohawk and Koei-Kan tattoo down the side of his scalp gave him a pillager’s appearance that just really brought home his brand of violence. The cool icicles on his shorts? They became synonymous with smelling salts.

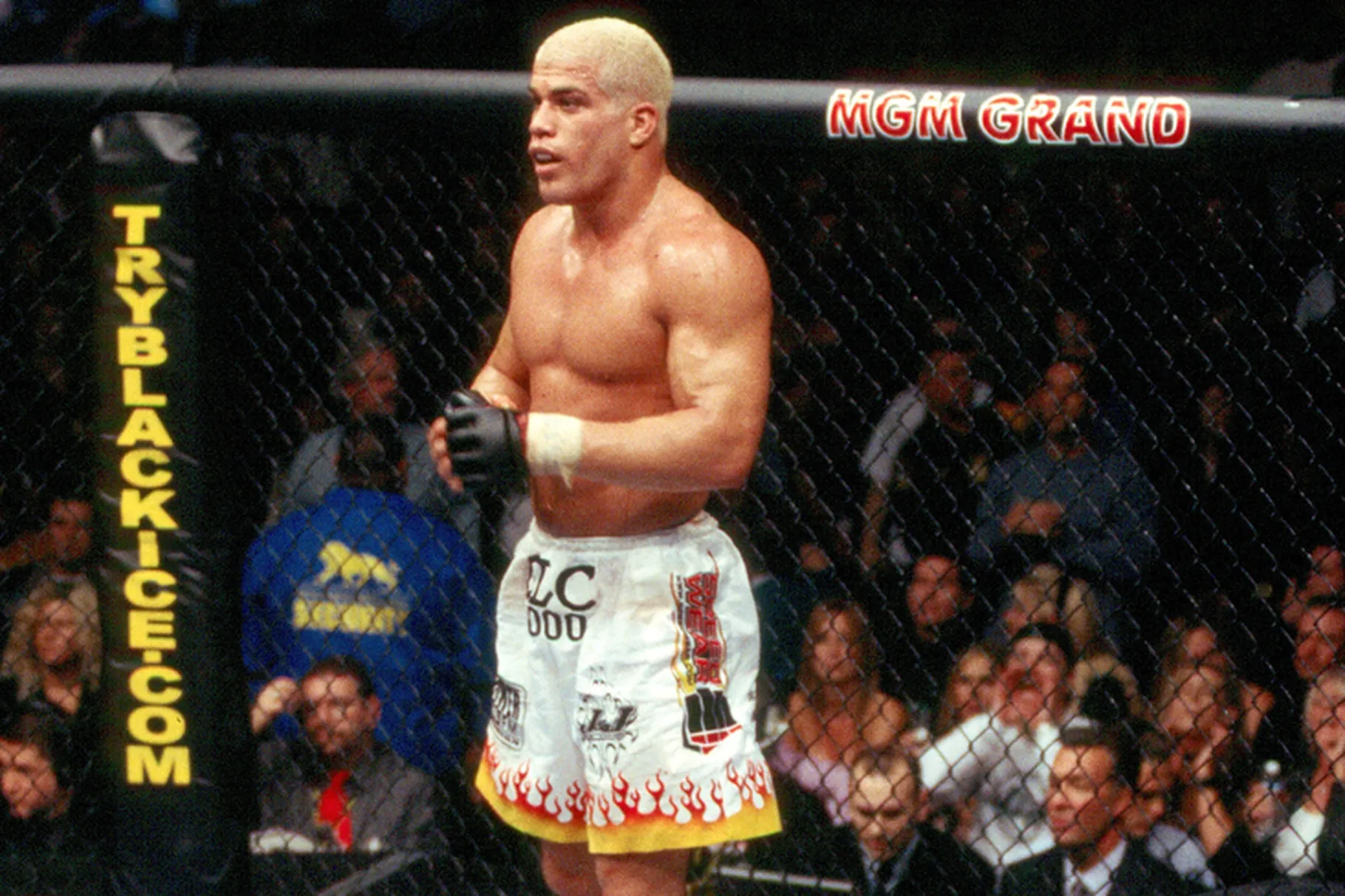

From 2004 to 2006, Liddell fought seven times. He won by knockout seven times. All of them were in Las Vegas, which was the Chuck Liddell capital of the world. Five of those bouts were title fights. All of them were pressure cookers. Two of them were against Randy Couture. The whole streak was bookended by arse-whoopings of Tito Ortiz. (That part of it, the whippings of Ortiz, felt almost ritualistic).

The “Iceman” was the fight game’s true rock star. It wasn’t just his fighting style; it was who he was and the way he lived. It was the late nights and boozing and velvet ropes and the pandemonium of public outings and adoring women. He walked with a badass hitch, and made his arms into an “X” with a loose pinky hanging out when paparazzi got in his grill. When he won, he threw his arms back and screamed like an alien was about to pop out of his chest. When not doing that, he was falling asleep during live morning talk shows in Dallas to the horror of its sober television hosts, and treating it all just like…eh, what’s for breakfast?

“Yeah, he was a rock star,” says his longtime trainer and friend John Hackleman, who was the first to introduce Liddell to nail polish. “He’d call me up and say, hey, we’re going on a private jet to so and so, and everything else got put on the backburner. And me, just as a trainer, not even the fighter, it was consuming most of my time. He was definitely living like rock star.”

At UFC 57, at Chuck-Randy III in Feb. 2006, Liddell was already the light heavyweight champion after having avenged a loss to Randy Couture at UFC 52. As always in trilogies, the math was showing patterns that corroborated with hunches. At UFC 43 Couture had woke the sleeping giant. At UFC 52, Liddell took the belt and made the first fight feel fluky. By UFC 57, the biker Hun from Santa Barbara was UFC’s version of Goliath, and Couture was in the role of David.

After he beat Couture in the third fight, the after party raged on. And on.

“I made a lot of enemies asking him to reel it in a little, both with the media and the sponsors and promotion and stuff,” Hackleman says. “But Chuck just had so much going on, and you can’t keep track of someone unless they want to be kept track of. My biggest thing was, I’d never even been to an after party. I was so conservative in the way I lived that I just couldn’t believe a fighter would do that kind of stuff. He was anti-everything I was, so I was always the last to know anything. It was hard to reel in that superstardom at that time.”

At UFC 62, in a rematch with Renato Sobral, Liddell waited for “Babalu” to wade in with his strikes to blast him with an uppercut early in the first round. For the next half-a-minute, he stalked him to the fence, peppering him with big shots flung from the hip, then to the ground, where he predatorily — almost casually — finished the job. It was his third title defense.

The after party was epic. And it raged on.

“He still went out a little bit, and that’s an understatement,” says Hackleman. “If I was different in a lot of other ways, like if I was more of a party guy or if I was one of his trainers instead of his trainer since day one, if I was like that I can’t imagine how bad it would have gotten.”

At UFC 66, the “Iceman” hit the high point of his career. That was the night he beat Tito Ortiz in a rematch from UFC 47. The bad blood between them had brought the public’s blood to a boil, too. Liddell exploded with a series of punches to down Ortiz in the third round for his fourth title defense.

Liddell, the legend, celebrated.

“Chuck had all kinds of celebrities who loved him, all these football and baseball players who worshipped him who I don’t even know because I don’t watch those sports,” says Hackleman, who for a decade was asked if he’s Chuck’s dad. “One time, Tony Robbins flew in to visit Chuck, and I look over and Chuck is just texting people and ignored Tony. I was like, what are you doing? I had to take his phone away.”

After 2006, the thing began to fall apart for Liddell. “There was signs that it was coming,” Hackleman says. He lost his next bout to Quinton Jackson at UFC 71, then the following fight to Keith Jardine at UFC 76. The end of the “Iceman” was near. After 2006, he went just 1-5, before retiring in 2010 after getting knocked out by Rich Franklin.

As the Liddell era closed out, Anderson Silva’s just got started. By 2007 they were two ships passing in the night.

And as for Leben, in his rocking chair moments with his grandchildren at his knee, he can truthfully say he fought the spectrum in a year’s time. He went from fighting Jason Thacker in 2005, who had no business taking off his shoes to get in the Octagon, to Anderson Silva in 2006, the greatest mixed martial artist we’ve known.

All challenges that came after fall somewhere in-between.

2005: The Griffin-Bonnar dream, from the footprint of reality

In the spring of 2005, the original TUF had its Finale at the Hard Rock Hotel in Las Vegas. When Stephan Bonnar and Forrest Griffin went to war, little did they know that much more than a six-figure contract was at stake.

Reality television has always been more real than we give it credit for. In real life, exploitation can be tolerated in exchange for such things as “visibility.” In reality TV, though, exploitation became the key ingredient to “your big chance,” and that cranks the knob to eleven for vicarious entertainment.

Nobody wants to die anonymous.

To this day the “Ultimate Fighter” franchise works on the tenant that its producers are plumbing the Earth’s great depths for that rarified talent that has gone hitherto undiscovered. There’s ore just under the surface, we’re told. By now, after umpteen seasons, we know we’re in the bargain bins for that talent. Fewer future champions are being made on TUF. At this point we are stockpiling the prelims.

Yet still there’s immense fun to be had watching people grope about for validation in, honestly, the realest of the “real” circumstances. Never mind the boom mics, the culmination of watching people act the fool in TUF is that we get to then watch them punch each other in the face. Other reality shows can’t boast as much.

The original Ultimate Fighter was a time buy that Zuffa did with Spike TV in 2005. It was a roll of the dice that smacked of desperation to position the fight game better into our collective conscience. Had it failed, like so much had between the dozen years of the UFC’s existence, Joe Lauzon would still be fixing computers. And there’s a real chance that so much of what we’ve come to be astonished by (FOX, Toronto, Nick the Tooth) would never have come to pass.

That first season of TUF had all the components, too.

It had Stephan Bonnar, who mysterious disappeared for a couple of shows (turns out he’d fled through the bathroom window in search of hooch and got busted), and to this day we don’t know who stole his beanie. There was Diego Sanchez, summonsing the energy from a lightning storm on the front lawn. There was Josh Koscheck, all peroxide and jocularity, prodding poor Chris Leben…and Leben spritzing on poor Jason Thacker’s bed…and Bobby Southworth mouthing off. Forrest Griffin shaved his head, and people kept getting drunk. There was Nate Quarry, and Kenny Florian fighting six weight classes out of his natural frame, and Mike Swick (who was still smarting about a loss to Leben in WEC the year prior, adding that elephant to the room).

In short, suddenly we had fighter back-story.

And the fights themselves were ridiculous. Even the well-known coaches, Chuck Liddell and Randy Couture, were props for this impromptu set-up. Remember when the contestants competed in games, like carrying Couture and Liddell on La-Z-Boys down the beach in a race? That still feels impossible.

Though there was a lot of talent on the show, even all that talent needed a nudge from time to time to do something as ridiculous as to lay hands on one another with intent to do harm. At one point, at the height of the mutiny going on behind the scenes with all these combustible parts, Dana White had to come down to the training center and have a word with everyone. His “Do you want to be a f—ing fighter” speech now belongs up there with Knute Rockne’s “Win one for the gipper” and The Gettysburg Address in fight game lore.

But it wasn’t until the TUF Finale on April 9, 2005, that the thing really took off. The headlining fight between Griffin and Bonnar was so mystifyingly good, so back-and-forth and frantic in pace and devoid of sound defense, that it created an old-fashioned groundswell. These days we like to think whoever was watching got on their phones and told those casuals who weren’t to tune in, and then those people called others, and those people still others, and pretty soon everyone was alive with the sound of leathersmash with their jaws dropped to the floor at what they were beholding.

“That fight was important,” says the third man in the Octagon that night, Herb Dean. “That’s the fight that got people interested in what we were doing. Those guys brought it, and everything about it kind of went perfect. Dana White, he came out and gave them both the award. It was a great day.”

The award was (and still is) a vague six-figure contract. But in this case, with the fight transcending all expectation, White awarded both men the contracts, because it was the right thing to do. White’s largesse was as central to the payoff as the fight itself. And that fight, with its show of pluck and determination and the willingness to swing freely, became the most valuable single event to ever happen to the UFC.

“When reffing, I can tell when a fight’s exciting, and that one I definitely could,” Dean says. “I was like, okay, these people need to start cheering right now. This is something special. Hardly ever do you see light heavyweights go at it with that type of pace.”

Dean, who came up in refereeing in the King of the Cage beginning in 1999, reckons the first UFC fight he officiated was at UFC 47, when Wade Shipp fought Jonathan Wiezorek. He’s been in the cage for some of the biggest fights on record over the years. He’s seen everything, but he says he had no idea of the magnitude of what he was watching at the Hard Rock Hotel that night.

“I didn’t know it would be that important at the time,” he says. “I remember it was a great fight and I was so happy that for the Finale, that these guys did it as good as it could get, but had no idea it would have that type of importance.

“I’ve been surrounded by mixed martial arts. From the inside I can’t really see how big it’s growing, because it surrounds me all the time. If I’m treading water in a big swimming pool, a little swimming pool, the ocean, the bottom line is your surrounded by water, you know what I mean? So I don’t have a great perspective.”

Bonnar and Griffin are now both tucked away in the UFC Hall of Fame, in no small part because they put on a fight that opened the floodgates to public enthusiasm. That bout, unbeknownst at the time to the fighters themselves, had the greatest stakes in the abstract sense. They were punching for a million futures, and eating punches for a million more.

At the time, who’d have thought that the UFC would grow so big?

“It’s really funny, but I did,” Dean says. “I was upset because it took so long, but maybe I don’t understand things the way I should. In the 1980s, we watched all kinds of things on TV. I’m not trying to take anything away from curling, but we watched people brush ice. I believe that fighting is the purest sport on Earth, because I think that all sports really are a fight.”

2004: When the west was still wild, and 50 was just a number

The year before TUF put the UFC on the map, 2004 was still like the Old West. But have so many strange elements ever come together like they did at UFC 46?

In the age of celebrating milestones, UFC 50 crept by without so much as a doff of the hat — and with 40,000 PPV buys, we all but gave the semi-centennial show the finger on its passing. The event was held in Atlantic City, and featured the 7-0 Georges St-Pierre, a prelim fixture to that point who’d just beaten Jay Hieron, against the dense-necked former champion Matt Hughes, who was already in the UFC record books with five welterweight title defenses.

The bout was for the vacant title, because B.J. Penn — who’d taken the belt from Hughes — had defected to K-1, and the UFC wasn’t about to let him walk with the accessory. Such were the times. That night, Hughes became a two-time champion when he caught St-Pierre in an armbar with just one second remaining in the first round. Had GSP held on that extra second for the clacks? Perhaps the Québécois would have named a day after him by now, like Long Island did for Chris Weidman.

The co-headliner at UFC 50 was a sad thing. An unknown fighter named Patrick Cote fought the company legend, Tito Ortiz. Cote was filling in for Guy Mezger on ridiculously short notice (four days) and was making his promotional debut. Ortiz? Though he was on a two-fight skid, he’d already fought in the UFC 13 times, including twice against Mezger, which brought about the rubber match that wasn’t happening. Cote getting the fight was an act of desperate cobble-work, but it sure fed some intrigue into his biographical details when he became a cast member on TUF 4. Ortiz, of course, won.

The whole thing was barely noticed. In comparison to UFC 100 — an immense dual-title card that had Dana White promising to jump off the roof of the Mandalay Bay if the PPV number topped 1.5 million (which it did, even White wisely didn’t) — UFC 50 felt like the culmination of not much.

“[UFC 50] was not even close to UFC 100,” Dana White says. “UFC 100 was huge.”

UFC 46 in January, on the other hand, was at least something. What it was exactly is hard to pinpoint, but its operating title — “Supernatural” — was certainly on the right track, given the confluence of names and circumstances. Looking back on it now, it’s like clicking through slides of the Old West on a View-Master. At the time, it was just the usual amalgamation of chaos and characters.

Consider the lot.

There were great stories still waiting to unfold, like Matt Serra, who in two years would pull off the upset of the decade, opening against Jeff Curran on the prelims. There was St-Pierre, who in two years would be the Goliath figure that fell to Serra, closing out those prelims. And right in between there was Josh Thomson, who in 2013 — nine years later — would find himself fighting for the UFC belt.

For all those, there was Karo Parisyan, who is now a UFC pariah for violations associated with nerves and nerve candy. And Hermes Franca, who lost to Thomson. Franca ended up in jail for sexually abusing an underage student at a Brazilian jiu-jitsu academy. And then there was the granddaddy of fight game folklorists, Lee Murray — you might remember him rolling out to the cage dressed disarmingly as Dr. Hannibal Lecter — who ended up authored a $50-million bank heist in the U.K., and is now serving a 25-year sentence in a Moroccan prison. Dana White would say later on, “he is a scary son-of-a-b—-, and I don’t mean fighter-wise.”

No, the people fighting on UFC 46 weren’t your usual sipping teas.

Heading into UFC 46, the breadth of Murray’s lore was simply that he’d knocked out Tito Ortiz in a bar fight in London in the wee hours after UFC 38. That bit of gossip made its way across the pond well ahead of his fight with Jorge Rivera, who showed up to Vegas so normal as to become conspicuous. It was to the point that Rivera knew he was fighting a myth as much as the man.

“I remember Murray had lots of hype following him,” Rivera says. “He had explosive power in both hands, and he had knocked Tito out in that street fight. So there was a lot of hype.”

After Murray submitted Rivera, Joe Rogan asked him about Tito Ortiz and Murray went into a chest-thumping alpha rant. Ortiz, sitting the front row, made a casual throat-slashing gesture back towards him that signaled his acceptance to the challenge.

“There was a lot going on, but I remember the upsets that night,” Rivera says. “B.J. Penn and Vitor Belfort both won, and with Belfort, it was a weird ending that I didn’t see that coming. I believe that was the fight Vitor announced his sister had been kidnapped.”

It was. Belfort sister Priscilla had gone missing just a few weeks before his title fight with Randy Couture in the main event, and that tragedy hung over the whole thing. Belfort fought anyway, yet the bout itself was a buzzkill, as just 45 seconds in Belfort glanced a punch off of Couture’s eye that scratched his cornea, thus prompting the cageside doctor to call it off.

Couture lost the light heavyweight belt on a fluky ordeal, and Penn — who was a cult figure by this time for his elasticity and Hilo warrior spirit — forfeited the belt he took from Hughes that night when he signed with K-1, setting up the Hughes-GSP fight at UFC 50.

Whatever it was about UFC 46, there something more going on than the usual bouquet of fates.

2003: When the fight world revolved around Bettendorf

Long before Brock Lesnar’s brute force and Cain Velasquez’s relentless pace, there was 6-foot-8 Tim Sylvia — a Bettendorf oddity that crashed out of the Miletich Fighting Systems and into history.

It feels like an old wives’ tale now, but there was a time that the 6-foot-8 Tim Sylvia ruled the heavyweight roost in the UFC. This was of course well before he showed up in Moosin: God of Martial Arts to fight strongman Mariusz Pudzianowski, and eons ahead of his enormously underwatched fourth fight with Andrei Arlovski in Quezon City. It was in 2003, right at that time people began to genuinely question just what was in the water out there in Iowa. Sylvia came out of the Miletich Fighting Systems, stylized by the no-nonsense former welterweight champion Pat Miletich, who had produced the likes of Matt Hughes, Jens Pulver and Jeremy Horn as well.

Miletich had built a fight factory in Bettendorf, which in itself has become memorialized over time like a battle sight of some old war.

Sylvia’s run started at UFC 41, when he fought Ricco Rodriguez for the heavyweight belt. Believe it or not, the chorus of “too soon for a title shot” that guys like Glover Teixeira hear these days stretches back to humanity’s earliest concerns, and that was the case for Sylvia, who had but one UFC victory under his belt from UFC 39. In that fight, Sylvia put a beating on Cabbage Correira at the Mohegan Sun that raised a few eyebrows. With his yeti-like frame, he was either a marketable oddity, or a genuine threat to the throne (and hopefully both).

The scene in Atlantic City that night was one of dissatisfaction, because in the co-main event B.J. Penn and Caol Uno fought to a split draw for the inaugural lightweight belt. Rodriguez, was coming off the biggest victory of his career against Randy Couture at that same UFC 39 card, and was making his first title defense. In his corner was Tito Ortiz, who was omnipresent at UFC events in those days, wearing his own light heavyweight belt backwards around his waist for the fans to get a load of. Nobody hogged spotlight quite like Ortiz when he was at the top of his game.

And in front of Rodriguez was the gangly Sylvia, who was something to the eye. His beard was carefully landscaped, accentuated by the swift lamb chops that stenciled down his cheekbone like a scythe, connecting to the mustache (which itself had plenty of plotlines). His shorts were tight; perhaps too tight. He wore the look of Sturgis, and that look fit into the heavyweight category quintessentially. It was uncanny. Here was a man who fully embodied his nickname of “The Maine-iac.” (To this day a bold choice for its hyphen and cleverness). (And to hear Miletich’s stories years later, a more apt nickname might have been “The Ego Maine-iac,” because Sylvia had an unflinching “me” streak).

Then the beginning of the Sylvia Era got ushered in, whether we were ready for it or not.

Ricco hit Sylvia with a flying knee early, and Sylvia smiled the smile of the afflicted before proceeding to crawl into Ricco’s guard and dropping some paws. A bit later, Rodriquez tried for an armbar, but Sylvia lifted him up casually and dumped him to the ground, like he was shaking off a playful toddler. Sylvia lumbered forward and threw a couple of heavy sandbags that missed awkwardly.

Finally, though, just past the halfway point of the first round, Sylvia threw a big right hand from orangutan distance that crashed into Rodriguez’s chin, and the Miletich clan knew their creation was alive. That shot put Rodriquez on ice, though Big John McCarthy waited to see the follow-ups. Sylvia went to the ground and missed the motionless easy target two out of four times, punching the wooden canvas instead. But it was over. Sylvia was the champion. The next thing we knew Miletich and Horn were descending on the scene and hoisting his bulk onto their shoulders.

“What’s up now?” Sylvia yelled. “What’s up now?”

What was up was his stock. Sylvia went on to defend the title against Gan McGee at UFC 44 before having his arm snapped by Frank Mir nine months later at UFC 48. Though the image was gruesome, he would rebound and end up winning the title against Andrei Arlovski at UFC 59. He would defend the title twice before losing it improbably to Randy Couture, at that time 43 years old, who once again played spoiler to tyranny.

For Rodriguez, the loss to Sylvia signaled the beginning of the end of his time in the UFC. “Suave” spiraled with losses to Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira and Pedro Rizzo from there, and wouldn’t pop up again until a year later in Juárez.

In 2013, Sylvia’s two title defenses as a heavyweight remain tied for the most in UFC history.

2002: Chandeliers and the first historical half

In 2002, the UFC’s first and only half show went down at the Bellagio. And looking back on it, what a night UFC 37.5 was.

In the UFC’s pay-per-view numbering system that has now set a course for infinity, strange things are bound to happen in the timeline. UFC 151, of course, went the way of the Anasazi; one day it just up and disappeared. And in 2002, there was the advent of the first (and last) decimal in the pantheon of whole numbers.

That’s when UFC 37.5 took place in Las Vegas, a show that was crammed in front of Zuffa’s visit to Royal Albert Hall in London for UFC 38 because the marketing was already well underway when the half measure was conceptualized. The reason for the six-bout featurette that would go off without the nuisance of prelims? The Best Damn Sports Show Period on Fox Sports Net. It was all about Fox even in those early aughts, just when exposure was at a premium, and Zuffa was shaking the dirt off of all the preconceived notions about cage-fighting.

Though it was the clubfooted cousin of the usual PPVs, cut in half by circumstance and opportunism, the historical value of UFC 37.5 was high.

The premise was that the best fight from the card, which was headlined by Chuck Liddell and Vitor Belfort, would be showcased in its entirety on the show’s “All Star Summer” celebration. That’s how Robbie Lawler and a St. Louis fighter named Steve Berger broke ground as the first in the UFC to ever appear on free cable television. Lawler, doing what he do, knocked Berger out early in the second round — which meant, the first ever UFC fight to hit the cable airwaves lasted five minutes and 27 seconds all told.

“Who they would show [on TBDSSP] I think was up in the air at the time,” says Benji Radach, who fought Nick Serra that night. “I know they were kind of favoring Lawler, because he had a really exciting fight with Aaron Riley the fight before that when I fought Berger. That was a really good three-round fight, and it was exciting, so it was up in the air but it felt like they were leaning his way. He was an up-and-comer, and he had a lot of power.”

Both Lawler and Radach carry the distinction of having fought on both UFC 37 and the hook, UFC 37.5. Just like in the days of Bronko Nagurski, fighters in 2002 needed only a drink of water and a slap to the rear quarters to turn around and fight again (so long as the commissions said it was cool). As MMA was still new to Las Vegas and Nevada — which the first big hurdle in the UFC’s resurrection from the SEG era — the Bellagio was as good a venue as any to take off the shoes and duke it out.

And what a scene it was.

In 2013 it might seem odd to hold a fight card in a ballroom with cascading chandeliers, where the appetites ranged more towards good sturgeon roe than they do towards heel hooks, but in 2002 the surrounding elegance was…well, it was what it was.

“If I remember right, in that ballroom, there was bleacher seating,” says Radach. “[The UFC] wasn’t quite as professional as it is now, with all the extra hype and everything. But it still was the UFC, and it was still the big show on campus. They didn’t have all the extra little thingies. Now you get this bag and little things in your room, it’s kind of a lot of bells and whistles to go along with the program.”

Amenities aside, there were other “firsts” in play that night in June on the half card. Joe Rogan, who has been converting casual people into defensive hardcores for years with his descriptive work towards such things as gogoplatas, made his debut as the UFC’s color man on the broadcast. Before then he was the backstage guy, interviewing the fighters.

And though most fights on the card ended in knockout or decision, he did get to call his first armbar when Pete Spratt torqued Zach Light’s arm at the midway point of the first round. After that the Serra-Radach fight was a regular Garden of Eden for jiu-jitsuphiles with a microphone.

“First of all I knew Nick Serra was a really good submission guy like his brother, Matt,” Radach says. “I remember him catching me in that triangle right off the bat, and he locked up. And it was right at the beginning of the fight, which is not a good spot to be in, because he’s fresh and he’s got you in a full triangle. Luckily I was able to escape that. I remember that fight I was just trying to stay out of his triangles.”

Radach would steer clear of Serra’s geometric pressure enough to get the decision in the end, just like Liddell would take care of Belfort on the scorecards at UFC 37.5. And Lawler, whose left hand might one day be enshrined in the UFC hall of fame even if the rest of his body is not, made the chandeliers sway to the rhythm of his brand of violence.

2001: The Italian word for fighting (and a touch of evil)

2001 was the changing of the guard in the UFC. That’s when Zuffa took over the company and had its first show at UFC 30 in Atlantic City. After that? Global dominance.

Even for all its bed bugs and misty veils of Aqua Net, Atlantic City was a boon for the UFC in 2001, if for no other reason than it wasn’t Lake Charles, Louisiana. The UFC could put on fights in New Jersey even in the Dark Times when virtually every other state held a crucifix up to it. Donald Trump — himself a rogue figure with occasional foresight — was more averse to conformity than he was to the pack of outliers who fought in the UFC, and his Taj Mahal was home to the last SEG era event to be held in the States.

That was UFC 28, on November 17, 2000, seven years, five days and a million court battles after the belligerent chaos of UFC 1 sent us off on this course.

When the UFC returned to the Taj three months later, at UFC 30, it was a whole new ballgame. After UFC 29 in Japan, the hydra of Dana White and the brothers Fertitta (casino owners Frank and Lorenzo) ignored the circling vultures overhead and bought the UFC. They spent two million dollars for the day’s blackest cloud. And at the time it was like they’d been sold beachfront property in Wyoming. Even the Italian word Zuffa, for all its slick lacquer and shine, felt like a fresh coat of paint on the old jalopy.

Yet the new regime had the audacity to bring with it a plan.

UFC 30 was branded as “The All New Ultimate Fighting Championship,” its poster featuring Tito Ortiz standing arms akimbo, like the top half of a centaur from the mythological past. Same gunslingers, but new vision…and deeper pockets…and inroads to Las Vegas. The Zuffa era kicked off with a pair of title fights. Tito Ortiz against Evan Tanner for the light heavyweight belt, and Jens Pulver against the Japanese import Caol Uno, for the lightweight strap.

All of that was of course window dressing for UFC 30’s real story. On February 23, 2001, Dana White began his journey to becoming the greatest ringleader the fight game has ever known.

“I knew the difference in the aspect that the new UFC were from Vegas,” Pulver says. “For me I was like, okay, if these guys from Vegas are buying this, they have the ability and the options and the desire to get us into Las Vegas. It was great to be in Atlantic City, but Las Vegas is the fight hub. You’ve got to get into Las Vegas. So when they bought it, that was one of the things on the personal side I just got real excited. They weren’t going to buy a company of this magnitude without having at least spoken to the Nevada commission. It made me real excited as a guy living in Iowa and having never been to Las Vegas before.”

Pulver had two shades of eyes and a tactical mean streak in the cage. He fought at UFC 28 when Bob Meyrowitz and company were still the spearheads. That night he beat John Lewis, and earned the heathen’s nickname of “Lil Evil” from Pat Miletich.

“I went with the ‘Lil Evil’ moniker because that was so hard to get,” he says. “I had to knock out John Lewis to get it. I didn’t want to be called the ‘Pulverizer.’ I thought, really, Pulver? Come on. It was actually going to be ‘Grumpy Evil Little Bastard.’ But we shortened it down to ‘Lil Evil.’

‘Lil Evil’ remembers meeting Dana White at UFC 28, as well as first hearing the deeply affluent caramel-toned voice of Lorenzo Fertitta. He remembers also jumping in the Fertitta private plane to go scope out Caol Uno, who was the welterweight champion in Shooto, in his fight against Rumina Sato in Japan. That was one day after UFC 29, the last of the SEG era, also going on in the greater metropolis of Tokyo.

“Yeah, I got to fly to with them to Japan,” Pulver says. “They were getting ready to bring me in and do the Caol Uno fight, and they always said we want the top guys, so we went out there and watched Uno defend his title. That’s how I met Lorenzo, Frank and Dana.